Synopsis

Sindh generates the highest revenues in the country, but its leaders give it the short end of the stick

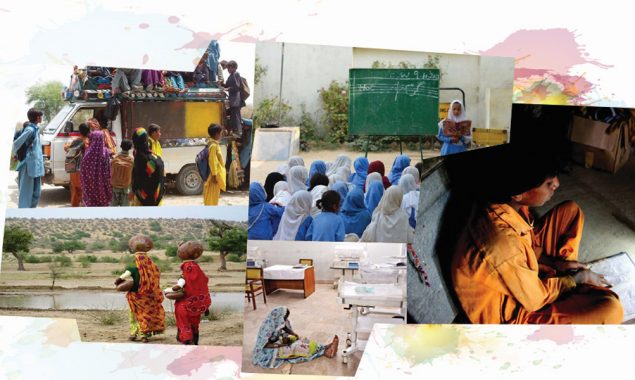

Although rural Sindh is approximately 100 kilometres away from Karachi, barring a few districts of the province, the rest depict a gloomy picture of deprivation and an abundance of issues that make life for the rural population extremely difficult. These issues include poor to no infrastructure, a bad law and order situation, dismal health and education facilities, an acute water shortage, and outdated agricultural practices.

And the last considering that around 40-to-45 percent of the people of rural Sindh depend on agriculture to scrape together a meagre living, toiling under the open sky, in often sweltering heat or biting cold.

“Farmers invest all their hard-earned accumulated assets in agricultural land without any security — but for the grace of God — hoping that their investment will be safe, and they will get good returns from their lands. But they have to face major problems in terms of water shortages, substandard seeds and fertilisers, and the price they are paid literally for the fruit of their labour — the rates for crops in the market,” said an agriculturalist.

Despite being an agrarian country comprising approximately 50-55 million acres of agricultural land, including over 12.7 million acres in Sindh, which have been divided into three command areas — Sukkur, Kotri and Guddu barrages — the country has had to import agricultural products for the 75 years since its inception, because of the ineptitude of successive governments.

Sindh Chamber of Agriculture Senior Vice President Nabi Bux Sathio stated: “Around 40-45 percent of the people of rural Sindh, except for those in Karachi and Hyderabad, are directly and practically associated with agriculture. They depend on making a decent living from the land.” However, he added, both progressive farmers and peasants have been facing multiple problems throughout the two main farming seasons of the year, the Rabi and Kharif seasons.

“One of the biggest problems is the water shortage throughout the year. Punjab claims it always releases Sindh’s share of water to the province, but tail-end growers are deprived of proper water and their agricultural lands remain barren.”

Sathio asked the government to form a comprehensive agriculture policy, directing growers of the different provinces to grow crops as per requirement so that they do not bear any kind of loss in case of surplus. He also urged the government to abolish any kind of subsidy and to promote mechanised farming in Sindh to ensure food security and to help farmers obtain good returns. He maintained that in the right circumstances this would be entirely possible, even at the present time of lockdowns and shutdowns of assorted businesses. “Only the agriculture sector has not been impeded or hit by the deadly Covid-19 coronavirus, as per practice, farmers already maintain a social distance and work under the open sky,” he said.

There are three parameters to secure a healthy return for crops. These include fertile land, ample or at least a proper water supply, and standard seeds. But nowadays, farmers are facing an acute shortage of urea and are being coerced to purchase it at almost double the rate. The government-controlled rate is fixed at Rs1,770 per 40kg bag, but it is being sold at rates ranging between Rs 3,000 and Rs 3,200.

Water rights activist Zulfiqar Halepoto said: “An acute water shortage is being witnessed in Sindh, as the province is not getting its proper share of water as per the 1991 Water Accord. The quality of water in Sindh is another issue. Furthermore, there is a politicisation of water, that can be witnessed from Guddu Barrage to Kotri Barrage, where political pundits and influential feudal lords enjoy a monopoly of Sindh’s water to irrigate their agricultural lands. A handful of favourite zamindars are even allowed to use direct outlets for this purpose.”

Halepoto added that the irrigation system of the country is divided into two segments — the Sindh Irrigation and Drainage Authority (SIDA), and the irrigation department. Both of these, he contended, pretty much fail to supply proper water to tail-enders and poor growers. And there are no local ponds or water reservoirs to store and conserve rainwater in the interior, where agricultural lands are often destroyed because of flood or drought.

To compound the sorry state of the province, there is bad to virtually no maintenance of law and order in both urban and rural Sindh. Said Sindh High Court advocate Ali Palh, who belongs to Tando Allahyar, “ There is literally no police presence in Jacobabad, Kandhkot, Shikarpur and Kashmore; there is no sanctity of chadar and chardiwari. And cases of theft and snatching are rampant in Tharparkar, where people depend on livestock farming to cater to the Karachi and Hyderabad markets. Livestock farmers are being deprived of their animals these days by gangs of thugs.”

He added that recently there were reports from Tando Mohammad Khan, a rural tehsil of Hyderabad, where two dozen people died from consuming poisonous liquor, but no remedial action was taken by any authority. And, he said, if social activists raise their voice, they are threatened with dire consequences. Palh continued, “In Gambat and Shahkot, armed ruffians demand that poor people pay protection money, failing which they or their family members will be killed.”

Another noted lawyer Imdad Unar disclosed that there are many flaws in the district and vehicular traffic police in connection with their training, lack of merit in appointment, politicised transfers, including the posting of top district officers like the senior superintendent of police (SSP), old unkempt rusty weapons, etc. Unar maintained that while Article 4, 6 and 7 of the Constitution pertain to such matters, they are not implemented in letter and spirit.

“If an educated man who cannot find work sells biryani by selling his wares committing a soft encroachment, he is arrested. But It should be taken into account that poverty induces crime,” he added. According to Unar, 70 percent of people in Sindh are forced to live below the poverty line because in many areas, including Badin, Thatta, Tando Allahyar etc, daily wage earners earn less than a dollar a day.

Vice Chancellor Sindh Agriculture University (SAU) Professor Dr Fateh Marri said recently in a programme: “The poor economic condition of people is worrisome in Sindh. Food inflation is skyrocketing, while daily-wage earned workers are being paid a pittance. How can they make both ends meet?”

As for Sindh’s health, education and roadwork sectors, said eminent nationalist and President, Sindh United Party (SUP) Syed Jalal Mehmood Shah, “There are some decent health facilities in Hyderabad, Sehwan, Jamshoro, Gambat, Sukkur and Nawabshah, but the rest of interior of Sindh is almost completely deprived of proper health facilities. People are thus forced to visit cities for medical treatment.”

He added that while the main Indus and National Highways, which come under the National Highway Authority (NHA), are in a reasonably decent condition, the section of Indus Highway from Jamshoro to Sehwan has been under construction for three years, while a section of the National Highway from Moro to Sukkur is in shambles. Commuters and locals who have to travel on these highways do so at some peril as road accidents are commonplace. Shah said that local roads leading to localities of various districts in Sindh are also in a ramshackle and run-down condition, because the PPP-led Sindh government has, in connivance with the district and local administrations, pocketed the funds for road infrastructure.

To add to Sindh’s woes, are its schools, particularly in the interior of the province, where really poor quality education is offered in dilapidated school structures by teaching staff that are, for the most part, not fully trained.

Awami Jamhoori Party (AJP) President Abrar Kazi launched a movement to save education a couple of years ago, and declared an education emergency in Sindh. The Sindh Chief Minister followed suit and also imposed an education emergency in the province.

Kazi said following this, the biometric attendance of teaching staff was initiated in educational institutions along with other remedial measures. However, these amendments were gradually done away with. Furthermore, Kazi contended, “Most primary schools have only one or two rooms, and there are no washrooms. There are around 44,000 primary schools and over 5,000 middle and secondary or high secondary schools which accommodate over 4 million students in the interior of Sindh.”

Educationists belonging to the public sector have repeatedly called for a sustainable education policy and a well-thought out plan to revamp educational institutions in the interior of Sindh where poor governance, inadequate funds and the lack of a proper syllabus, in addition to untrained, ineffective teachers, and an improper deployment of subject teachers in primary, elementary, secondary and higher secondary schools render an abysmal quality of education.

So far however, there seems to to no light at the end of this tunnel.

Read More News On

Catch all the Nawabshah News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Follow us on Google News.