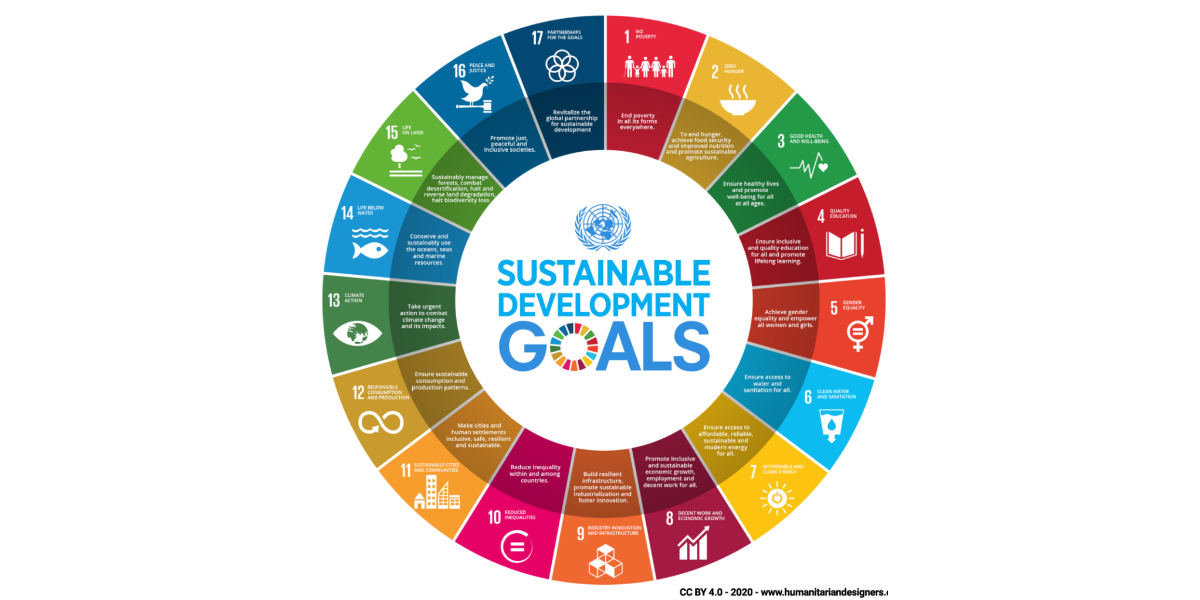

Times Higher Education (THE) released the 2022 Impact Rankings leading to chest-thumping by Pakistani universities and their staff. One university proudly displayed a huge banner saying, “tum nay kur dikhaya”. Times Higher Education Impact Rankings measure and reward a university’s impact on the society and its public good, framed through the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals. According to the Times Higher Education research, sustainability is becoming such an essential issue for prospective international students that some say they would be willing to pay higher tuition fees to study at a university with a strong reputation.

Can any educated Pakistani agree with this list that places LUMS and NUST below all others mentioned? Sustainability efforts at the universities are secondary at best for the students in Pakistan. Would you choose a university with a poor reputation for teaching and research if it had a better reputation for sustainability? Unfortunately, Pakistani students and their parents are duped by the aggressive car salesmen type “admission officers” into believing the “impact rankings are proof of good education”.

“Institutions provide and sign off their institutional data for use in the rankings,” the Times Higher Education website noted. Imagine a back office where a creative university staff is feverishly manufacturing evidence that their university is top-notch. It is not that difficult to get on the list.

There’s nothing wrong with the enterprises’ arrogant self-assertion, but there is something odd about educational institutions using third-party validation to sell more (enrol more students). And something is disquieting about the educators using rankings issued by QS, Times Higher Education, or any other body to validate or prove how they compare to everyone else.

Flawed methodologies have negative consequences. The rankings are manufactured for profit all around the world. I’d want to call attention to a profoundly problematic assumption shared by many in academia: the notion that there is, or could be, a meaningful link between a rating, on the one hand, and what a university is and does in contrast to others, on the other.

The University of Southern California’s graduate school of education removed itself from the rankings last year after discovering a “pattern of errors” in the data. A few weeks later, the dean of the Temple University’s Business School was sentenced to 14 months in prison after being convicted in federal court of transmitting false information to the US News and World Report to increase the institution’s status. Claremont McKenna College, George Washington University and many more colleges have manipulated statistics to improve their rankings.

The rankings feed the misconception that the wealthiest and the most selective colleges have a monopoly on excellent education and fail to acknowledge public universities that emphasise on access and affordability and forget to give enough credit to the unique characteristics of specific campuses.

But the ultimate issue with the rankings doesn’t lie with the cheaters. The problem is the rankings themselves. They can be a counterproductive way for the families to pick schools — for example, a much less expensive university might offer an equal or better education than a more highly ranked but costlier one.

Can Pakistani universities get in trouble for faking the data to attract unsuspecting students? Not yet. Because when a Pakistani university is ranked higher in any international poll, it becomes almost sacrilegious to question the integrity of the result.

It is interesting to note the company behind both QS and Times Higher Education rankings. RELX, Elsevier’s parent company, had $9.8 billion in revenues in 2019. (Elsevier’s profits account for around 34 per cent of RELX’s total profits). In 2018 Swedish and German research institutes announced that they were cancelling all Elsevier subscriptions due to the concerns about the sustainability, unfair pricing arrangements and a general lack of value. Within scholarly communications, Elsevier has perhaps the single worst reputation. With the profit margins of around 37 per cent, better than Apple and big oil companies, Elsevier dominates the publishing landscape by selling research back to the same institutes that carried out the work.

Throughout the methods, you can see an overwhelming bias towards Elsevier products and services, such as Scopus, Mendeley and Plum Analytics. These services provide metrics for researchers, such as citation counts and social media shares, as well as data-sharing and networking platforms. How is it reasonable for a multibillion dollars publishing corporation to not only produce metrics that evaluate publishing impact but also to use them to rank the Higher Education Institutions?

It is relatively simple to skew QS ranking in your favour. All you need is a handful of friends responding to a survey and you will rank better in ‘employability’. Guess who provides the list to QS for survey questions? The university that wants to move up a few notches above in the ranking.

Bottom line: You can manipulate the university rankings if you have resources and the universities may consider it a marketing expense to build the brand. However, in all of this, the students lose time and money.

(The writer is the CEO of Iqra University Extension)

Catch all the Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Live News.

Read the complete story text.

Read the complete story text. Listen to audio of the story.

Listen to audio of the story.