Born in Karachi in 1876, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah rose from a disciplined barrister to one of the sharpest constitutional minds the Indian subcontinent had ever produced. Calm, calculated, and uncompromising on principle, he believed in law over chaos, dialogue over disorder, and rights over rhetoric. Where many relied on street agitation, Jinnah fought his battles in courtrooms, councils, and negotiations.

Against overwhelming odds, he became the sole constitutional voice of millions. Pakistan was not gifted, it was argued, negotiated, and won through a relentless political struggle grounded in legality and reason. Even in fragile health, Jinnah carried the burden of a new state on his shoulders, leaving behind a nation built on vision, resolve, and dignity.

Architect of a New Nationalism

Jinnah’s most enduring contribution was the articulation of a new political nationalism later described as the Two-Nation Theory which challenged the Congress Party’s claim that India constituted a single nation. Jinnah argued that Muslims of the subcontinent were not merely a religious community but a nation with a distinct outlook on life, shaped by Islamic history, culture, ethics, and social organization.

This nationalism was not rooted in theological dogma but in political reality. Jinnah invoked the principle of self-determination, contending that a Hindu-majority Congress was unwilling to provide durable constitutional safeguards for Muslim identity, representation, and interests in a future independent India.

Islam as Ethics, Not Orthodoxy

Contrary to later misinterpretations, Jinnah neither advocated a theocratic state nor supported the fusion of clerical authority with political power. He viewed Islam as a civilization and ethical framework, emphasizing justice, equality, and fair play values compatible with democracy, constitutionalism, and the rule of law.

As Sir Aga Khan III observed, Jinnah sought to unite conservative and progressive Muslim thought. He was a modernist who believed Islamic principles could inspire a democratic society without enforcing puritanical or coercive religious injunctions. The idea of a state patronizing religious extremism was alien to his worldview.

From Unity to Separation

Jinnah’s early political career was marked by his commitment to Hindu-Muslim unity. A member of both the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, he played a central role in the Lucknow Pact of 1916, which secured constitutional safeguards for Muslim representation. For years, Jinnah believed that a federal India with legal guarantees could protect Muslim interests.

This belief shattered after the Congress’s rejection of minority safeguards in the Nehru Report (1928) and the discriminatory policies of Congress provincial governments (1937–39). These experiences convinced Jinnah that Muslim rights would remain vulnerable even under a federal system.

In response, Jinnah presented his historic Fourteen Points (1929) a constitutional charter of Muslim demands. When these, too, were ignored, the Muslim League gradually shifted from federalism to the demand for a separate homeland.

The Demand for Pakistan

By 1940, Jinnah openly described Muslims as a nation entitled to a homeland in the Muslim-majority regions of northwestern and eastern India. While he increasingly used Islamic idiom to mobilize Muslim opinion, he consistently rejected the idea of a religious state.

In an interview with British journalist Beverley Nichols in 1943, Jinnah clarified:

“Islam is not merely a religious doctrine but a realistic and practical code of conduct… I am thinking in terms of life—our history, culture, laws, and outlook.”

Pakistan, therefore, was conceived as a territorial nation-state, not a universal religious polity. Its feasibility rested on the geographical concentration of Muslim populations, not on a claim to rule all Muslims of South Asia.

Equal Citizenship and Minority Rights

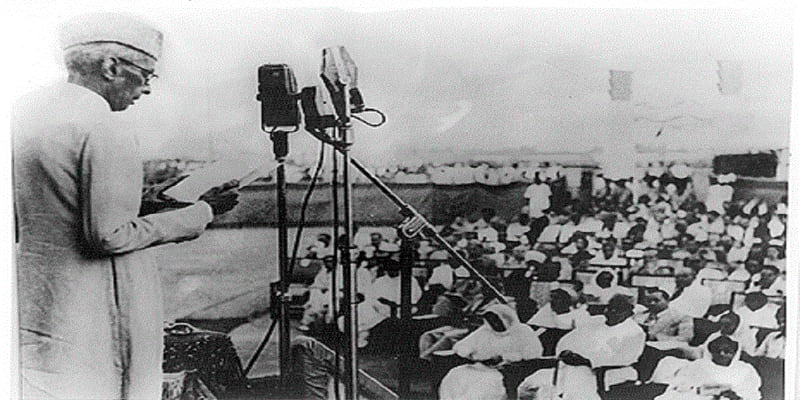

Jinnah was acutely aware that Pakistan would be home to non-Muslims. The Lahore Resolution (1940) explicitly guaranteed protection of minority rights. This commitment reached its most eloquent expression in Jinnah’s August 11, 1947 address to the Constituent Assembly, where he declared religion a personal matter and affirmed equality of citizenship.

Non-Muslims were included in Pakistan’s first federal cabinet, and Jinnah personally urged minorities to remain in the new state. These actions leave little doubt that Pakistan was not envisioned as a Sharia-enforcing religious state.

Post-Jinnah Distortions

After Jinnah’s death in 1948, religious political parties—many of which had opposed Pakistan—began promoting the idea that Pakistan was created “for Islam.” Later, military regimes, particularly under General Zia-ul-Haq, institutionalized a narrow and orthodox interpretation of Islam to legitimize authoritarian rule. Jinnah’s words were selectively quoted and taken out of context to support policies he never endorsed.

A Constitutional Legacy

Pakistan’s founders envisioned a modern, democratic, constitutional state rooted in the rule of law, pluralism, and equal citizenship. Islam was to serve as a moral compass not an instrument of coercion. Any attempt to transform Pakistan into a puritanical or violence-prone state departs fundamentally from Jinnah’s political ideals.

As historians from Beverley Nichols to Stanley Wolpert have observed, Jinnah was not merely a politician he was a statesman who altered the course of South Asian history through constitutional struggle. His legacy remains a reminder that nations are best built not through extremism, but through law, reason, and principled leadership.