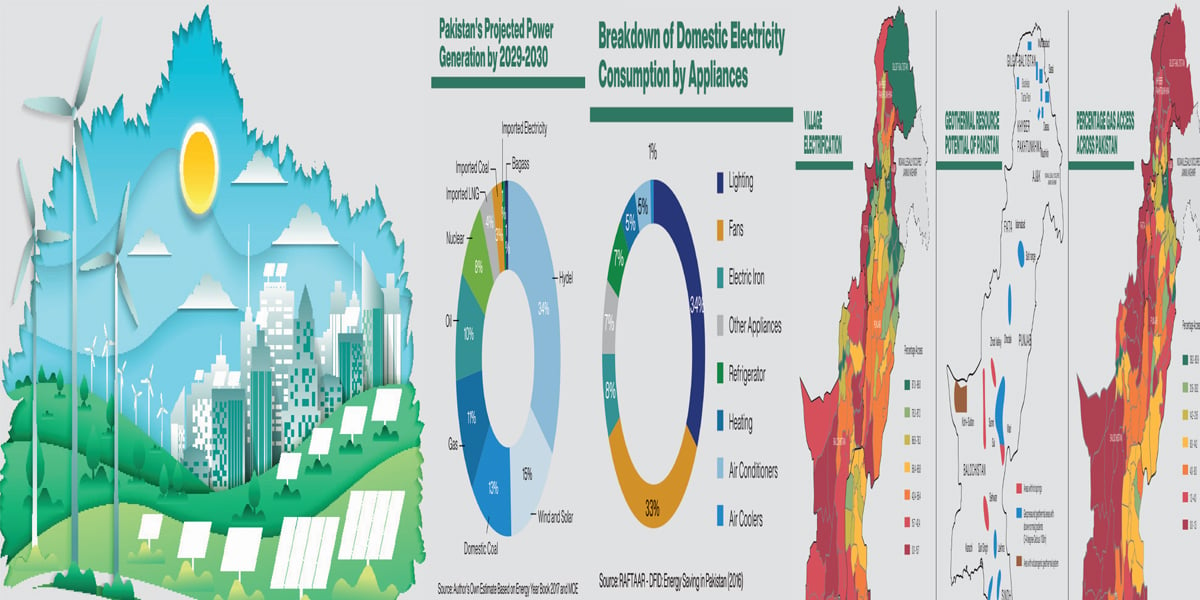

The majority of Pakistan’s energy supply is dominated by oil and gas, which counts for 80 per cent of its energy mix. The country mainly imports oil from Saudi Arabia and gas from Iran. In addition to this Pakistan consumes large quantities of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) and coal. The nation has a mere four power plants with a combined total capacity of 755 megawatts, while three more are being constructed. Nuclear energy accounts for roughly 1.9 per cent of the energy production, while hydropower stands at 13 per cent. Other renewable energy sources have a nearly negligible share.

Historically, Pakistan has always been an energy importer and is highly dependent on fossil fuels. However, with rising global temperatures and the increasing costs of oil and gas imports, more and more countries are looking to alternative sources of power. Ones that are cheaper and climate friendly in the long-term. As a country that risks facing a disproportionately high amount of climate related catastrophes, should the current warming trends continue, Pakistan needs to seriously consider diversifying its energy mix not just for the sake of electricity provision but as a precautionary measure against climate crises.

A country at risk

Pakistan faces multiple natural threats due to its geographical diversity and its varied climate. At the moment, it faces recurring heatwaves, droughts, floods, landslides, storms and cyclones, which are only expected to increase over the next few years.

These natural calamities already disrupt the livelihoods of locals and the economy of the nation. In Pakistan’s future, the science points towards increased temperatures far above global averages. The World Bank Country Risk Profile put Pakistan among the top risk-prone countries when it comes to climate change.

Pakistan regularly experiences some of the highest maximum temperatures in the world, with an average monthly maximum of around 27°C and an average June maximum of 36°C, while many regions experience temperatures of 38°C and above on an annual basis. A large section of the population is exposed to risks of heatstroke, with over 65,000 people being hospitalised with the stroke during the 2015 heatwave experienced in Sindh, of which 1,200 died. An estimated 126 heatwaves have been experience in Pakistan between 1997 and 2015, coming down to an average of seven heatwaves per year – a trend that is increasing. According to a WB report, scientist have identified Karachi and Lahore as the most adversely affected cities when it comes to extreme heat and the high mortality associated with it. Depending on the emission pathways, the probability of heatwaves could increase by three per cent to 23 per cent.

Furthermore if temperatures continue to rise, two primary types of drought may affect Pakistan; meteorological, usually associated with a precipitation deficit; and hydrological, usually associated with a deficit in surface and subsurface water flow, potentially originating in the region’s larger river basins. At present Pakistan faces an annual median probability of severe meteorological drought of around 3 per cent according to the Standardised Precipitation Evaporation Index.

Additionally, according to the World Resources Institute Global Flood Analyzer, AQUEDUCT, as of 2010 the population annually affected by flooding in Pakistan is estimated at 714,000 people and the expected annual impact to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is $1.7 billion. The are a consequence of increased climate change and development. Both these factors are likely to increase, and in turn increase these figures. By 2030, climate change alone is expected to increase the annually affected population by 1.5 million people, and the impact on GDP by $5.8 billion.

All these factors will adversely impact the natural resources available to the citizens of Pakistan and in turn damage their livelihoods and homes. While increases in the severity of extreme events of both flood and drought seem likely, there is some uncertainty regarding the long-term outlook for water resources in Pakistan. Uncertainty surrounds projections of change in annual rainfall, some shifts in seasonality seem likely. In the context of Pakistan’s heavy reliance on the Indus Basin for its water resource, the uncertainty around future glacial change is significant. According to the United Nations Development Programme, while in the short-term the climate change impact on water resources in Pakistan may be of lesser significance in comparison with the issues presented by growing human demand for water and other issues, including the poor efficiency of Pakistan’s irrigation and water storage systems, the long-term temperature rises will result in glacial loss. This will create reductions in the runoff which feeds the Indus River, as well as changes to its seasonal profile.

Pakistan’s coastline holds considerable vulnerability to sea-level rise and its associated impacts. Meteorologists suggest that without adaptation around one million people will face annual coastal flooding between 2070–2100. The largest area of vulnerability is the Indus Delta, around 4,750 kilometres of which sits below two metres above sea-level. It is estimated that around one million people live in the Delta. Meanwhile, saline intrusion continues to be a major challenge in the coastal zone, degrading land quality and agricultural yields. These issues are likely to intensify, affecting many marginal and deprived communities

Land and Soil degradation is also a major area of concern. There is significant potential for climate change to drive an increase in the land categoriaed as hyper-arid (the driest category) under high emissions pathways. This phenomenon has already been documented in some regions, as droughts become more frequent in arid and semi-arid areas. Potential impacts of the expansion of drylands and desertification include the sedimentation of reservoirs, generation of dust storms, and loss of biodiversity.

Energy Inequity

According to the World Energy Outlook 2016 statistics, at least 51 million people in Pakistan, representing 27 per cent of the population live without access to electricity. Furthermore, the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), in its annual State of the Industry Report, concluded that approximately 20 per of all villages, 32,889 out of 161,969, are not connected to the grid and those households that have electricity access experience daily blackouts. Therefore according to NEPRA an estimated 144 million people across the Pakistan do not have reliable access to electricity. As a result, Pakistani households use a mix of technologies to power their homes and businesses.

More than 50 per cent of the population, mainly in rural Pakistan, relies on traditional biomass for cooking, including firewood, agricultural waste and dung cakes. Additionally, many poor households are forced to invest up to 25 per cent of their monthly income in fuel, kerosene and batteries due to the dysfunctional market. In general, non-electrified households spend an estimated $2.3 billion a year on everything from candles, to kerosene lamps, to battery-powered torches. Due to poor distribution networks, households in rural areas using LPG as fuel pay up to 10 times more than urban households that benefit from subsidised natural gas for residential use.

Access to electricity varyies, with more than 90 per cent electrified households in urban areas and only 61 per cent in remote rural area.

A new strategy

The high costs of electricity production and increasing demands have put the government between a rock and a hard place. The Centre has encouraged consumers to move towards electricity to meet their energy needs so that gas may be saved for heating and industrial activities. Not only is this incredibly harmful for the country’s biodiversity and climate integrity, it is also largely unrealistic to assume that it is going to be successful.

This is because, Pakistan produces two-thirds of its electricity from fossil fuels, and the recent hike in petroleum prices means a shift towards electricity will be increasingly expensive for consumers.

The federal government recently set the price of petrol at Rs Rs159.86 per litre, and increased the electricity tariff by Rs1.68 per unit, which is nearly a 14 per cent hike. This revision has left the cost of electricity per unit at Rs24.33 for most domestic consumers, which is almost double compared to the average unit cost per unit of electricity generation, at Rs12.96.

As the country to looks to coal and other non-renewable resources to meet energy needs, such price hikes and shortages are continued to be expected. A shift towards green energy may be the solution.

A conversation around using renewable resources, locally found in Pakistan for energy generation is not a new one. The country have long aimed at achieving large-scale renewable energy production. However, as it stands Pakistan has set its target at achieving five to six 6 per cent of its total on-grid electricity supply from renewable sources, excluding large hydropower, by 2030. The country’s total installed power capacity in 2016 stood at 26 gigawatts, of which only 4.2 per cent was from renewable energy.

This is disappointing mostly because Pakistan is blessed with a high potential of renewable energy resources, but so far only large hydroelectric projects and few wind and solar projects have been invested in by multiple successive governments.

Wind:

Pakistan has a potential for wind energy specially in the southern coast and coastal Balochistan. The wind speeds average at 7 to 8 miles per second at some sites along the Keti Bandar-Gharo corridor.

Particularly in the southern regions of Sindh and Balochistan, the technical potential of wind power is very high. Along the 1,000 kilometre coastline wind speeds range between 5 and 7 miles per second. The potential capacity of wind energy alone is estimated at 122.6 gigawatts per year. This is more than double of the country’s current total power generation level. A newly completed wind farm in Gharo, is the first in a series of wind corridors being constructed to reduce the country’s energy deficit.

Solar:

Similarly, Pakistan’s solar potential is estimated to be over 100,000 megawatts. Irradiation across the country is around 4.5 to 7.0 kWh/m²/day. If chooses to, the country could implement the use of solar energy in many different sectors. For instance, more than 40,000 villages are so far from the grid that it is extremely costly and uneconomic to extend the electricity supply to these locations. However, this also makes them the ideal candidates for village electrification through solar home systems, which would generate enough electricity to meet their energy needs. Solar Water Heaters and Geothermal Heat Pumps are also a great investment opportunity, given that only 22 per cent of the population has access to the piped natural gas conventionally used for heating and cooking.

Aside for household electrification, solar power can also play a great role in the agriculture industry. Solar powered water pumps can be used as substitutes for the 260,000 tube-wells that traditionally operate under sanctioned electrical load of 2,500 megawatts, and the 850,000 diesel water pumps which use 72,000 tonnes of oil equivalent of Diesel annually. Additionally, Pakistan has over 500,000 street lights with a sanctioned load of over 400 megawatts. If these were replaced with solar lighting, this could further ease the energy burden.

Biomass:

As much as 21.2 million hectares in the country is cultivated land, or which nearly 80 per cent irrigated. This means that the biomass availability in Pakistan is also widespread, with approximately 50,000 tonnes of solid waste, 225,000 tonnes of crop residue and over one million tonnes of animal manure being produced daily.

It is estimated that potential production of biogas from livestock residues is 8.8 to 17.2 billion cubic meters of gas per year. Meanwhile, the sugar industry in Pakistan also generates electricity from biomass energy for utilisation in sugar mills with bagasse being used to produce an is estimated at 5,700 gigawatts of electricity annually – about six per cent of Pakistan’s current power generation level. In fact in the present energy crisis, the federal government allowed sugar mills to supply their surplus electricity, at a limit of 700 megawatts, to the national grid. In total sugarcane bagasse may be able to generate 2000 megawatts of electric power annually.

Hydroelectric:

Large Hydroelectric power generation sites have proven themselves to be the cheapest source of electricity for Pakistan. Despite the high availability of hydroelectric power sources, there are relatively little investments being made in this sector and thus hamper the maximisation of this as a potential major energy source for the national grid.

Smaller site, with less than 50 megawatt power generation are available throughout the country. Therefore, the micro hydropower sector has become relatively well established. Since the mid 80s micro-hydroelectric power plants supply electricity to as many as 40,000 rural families. However, most of these plants are community-based and are situated in the Northern Areas of the country and Chitral. Currently, small hydropower is considered to be one of the most promising option for off-grid power generation, however, it has the scope to become a much larger industry. The potential for micro-hydroelectric power, under 100 kilowatts, is estimated at 350 megawatts in Punjab and 300 megawatts in northern Pakistan.

Going green?

The demand for electricity in Pakistan has increased drastically over the last five years, and over half of this demand originates from the Punjab province where the majority of the population resides. Households are mainly responsible the increase in demand. This is not to say however, that the high demands of industries and local businesses are being met. While prices of fossil fuels are rising, so too are the living standards of the average Pakistani. The recent rise in demand is largely attributed to the widespread installment of air cooling and conditioning systems, specially in urban areas.

Overall Pakistan is struggling with a large gap between electricity supply and a demand. Adding renewable sources of energy production could significantly reduce this gap, meeting both the country’s electricity needs and climate goals.