Some Justice Department officials remain silence at the search of Mar-a-Lago

The Justice Department's public disclosures about investigations, particularly the extensive criminal investigation...

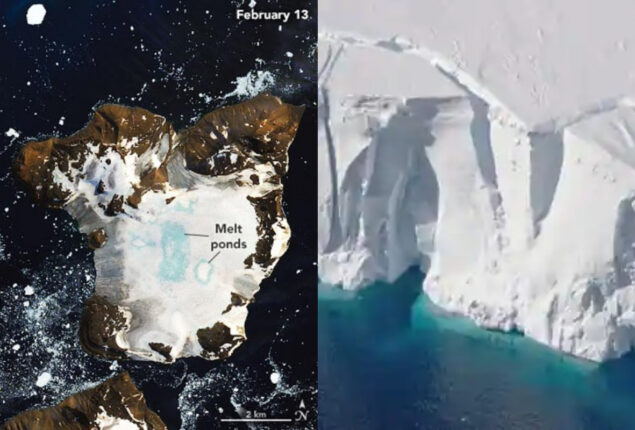

Satellite photos

A satellite analysis on Wednesday revealed that the world’s greatest ice sheet has lost twice as much ice over the past 25 years as previously thought because the coastal glaciers in Antarctica are losing icebergs faster than the environment can restore the melting ice.

It is now more important than ever to be concerned about how quickly climate change is weakening Antarctica’s floating ice shelves and accelerating the rise of the world’s sea levels, according to a groundbreaking study conducted by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) close to Los Angeles and published in the journal Nature.

The main conclusion of the study was that the net loss of Antarctic ice from chunks of coastal glaciers “calving” off into the ocean is almost as great as the net loss of ice that scientists already knew was occurring due to thinning brought on by the melting of ice shelves from below by warming seas.

The investigation found that thinning and calving, when combined, have decreased the bulk of Antarctica’s ice shelves by 12 trillion tones since 1997, which is twice the prior estimate.

According to JPL scientist Chad Greene, the study’s principal author, the continent’s ice sheet has lost about 37,000 square kilometers (14,300 square miles) of its area in the previous 25 years due to calving alone, an area that is almost the size of Switzerland.

In a NASA press release announcing the findings, Greene stated that “Antarctica is collapsing at its edges.” And the continent’s enormous glaciers tend to accelerate and enhance the rate of the rise in the ocean’s surface when ice shelves weaken and shrink.

There may be severe repercussions. According to him, 88% of the world’s ice could raise the sea level.

It takes thousands of years for ice shelves, which are permanent floating sheets of frozen freshwater tied to the land, to form. Once formed, they function as buttresses to hold back glaciers that would otherwise readily slip into the ocean, raising sea levels.

The long-term natural cycle of calving and regrowth regulates the extent of ice shelves when they are stable.

However, in recent decades, warmer oceans have damaged the shelves from below. This phenomenon has already been observed by satellite altimeters, which track changes in the height of the ice. According to NASA, losses from 2002 to 2020 averaged 149 million tonnes per year.

Catch all the International News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Follow us on Google News.