Synopsis

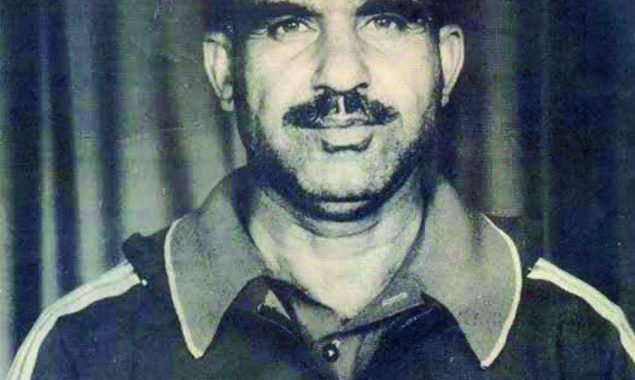

Khaliq was once the fastest man in the continent during his illustrious 20-year career

Khaliq was once the fastest man in the continent during his illustrious 20-year career

It has been 33 years since the death of his father but Mohammad Ijaz is still struggling to get his parent the respect he deserved.

Most people in Pakistan were unknown of this legend till 2013. They didn’t know about the athlete who was commonly known as the fastest man in the Asian continent.

They didn’t know about the icon who went to India and set two Asian records in 1954 which earned him the title of ‘The Flying Bird of Asia’ by the then India Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. They didn’t know about the great Abdul Khaliq till they watched the Bollywood movie Bhaag Milkha Bhaag.

There was a small yet powerful character in the movie, based on the life of India’s legendary sprinter Milkha Singh, named Abdul Khaliq who was shown as a bumptious man. It was the first time many of us heard the name Abdul Khaliq.

It was shown in the movie that Singh has a race with his Pakistani counterpart and he comes out on top.

While it was true that Singh had outrun Khaliq in that particular race and then President General Ayub Khan named him as ‘The Flying Sikh’, but as contrary to what is shown in the movie, the Pakistani athlete was far superior to his Indian compatriot, winning 63 international medals for the country.

“Bhaag Milkha Bhaag had portrayed Khaliq as a little negative character,” said Ijaz when asked about how he felt seeing his father as an antagonist in the movie. “However, all I wanted was to make his name alive, which is why I allowed Milkha Singh to use his character in the movie. I had planned this move carefully. I knew that it will work in our favour.”

When Singh called Ijaz to ask for permission regarding adding the character of his father in his biopic, he complimented his father’s rival, saying how big an athlete he was.

However, Singh’s reply filled his heart with pride and his eyes with tears. “Ni yar tera bapu bho wadda athlete si, main ik dafa us nu jeet gya te Flying Sikh bangya, meri gal bangai, tera bapu bho wada athlete si [No, your father was a legendary athlete, I defeated him once and became the flying Sikh, I got lucky, but your father was a huge name],” he said.

In 2014, after the release of Farhan Akhtar’s flick, Ijaz started collecting his father’s records and footage to build his legacy and he intelligently used Khaliq’s character in the movie for the purpose.

Khaliq had a glorious career spanning more than two decades. He belonged to a family of athletes, all his brothers had represented Pakistan on the international stage.

For Khaliq, it all started when a few army personnel saw him playing pir kabaddi in Chakwal, a kind of kabaddi whose playing field is 300 to 400 metres long. A player touches a man of the opponent team and runs all the way to his own court.

They identified his potential and offered him to join Boys Army. Though Khaliq’s family was financially stable, he realised that the opportunity could make the situation better. Against the will of his father, who was a Math’s teacher and wanted his son to pursue his education post 8th grade, he availed the opportunity and moved to Attock.

He was an extraordinary performer in the army, shining on the playing fields and kept climbing the ladder.

Eventually, he became a national athlete. His first prominent international appearance came in the Indo-Pak Games in 1952.

In 1954, he competed in the Asian Games and set an Asian record of 10.6 seconds in a 100m sprint, bettering India’s Lavy Pinto’s feat of 10.8 seconds. He won a Gold and a Silver medal in 100m and 4x100m relay, respectively, for his country.

Indians and Pakistani athletes came once again face to face in 1956. When Khaliq reached India, their media did not respect his stature and called him a player of 100m only, claiming that he will not be able to even touch the dust of Pinto’s shoes, who was arguably the best in the 200m category.

“It upset him,” shared Ijaz about his father. “He said ‘they shouldn’t have done it’. He was determined to prove them wrong. The next day, he broke his own Asian record and ran 100m in 10.4 seconds.”

When it came to the 200m race, he outran Pinto and registered a new Asian record of 21.1 seconds in 200m. It was where Nehru called him the Flying Bird of Asia.

Afterwards, he went to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics and reached the semifinals of the 100m and 200m competitions. He ran 100m in 10.5 seconds, while the third was 10.4 seconds, which deprived him of a spot in the final. He was among the fastest seven athletes in the world.

“An Australian newspaper wrote that if Khaliq was not burdened and only ran 100m and 200m, he would have done better. He was competing in 100m, 200m and 400m relay,” reiterated Ijaz.

The legendary sprinter hung his boots in 1977-78 and walked into the dark. After retiring from the Army as Soobedar, he joined Pakistan Sports Trust, PSB now, but did not live a high-profile life.

“My father used to walk barefoot to meet his mother in his village, kiss her feet and sit on the floor in respect. He used to wear dhoti and kurta in his native town. No one could tell that he was such a decorated athlete,” reminisced his son. “His friends used to tell him to dress better and he responded saying he is not a celebrity here, it was his village, his people, ‘I am one of you. I have three-piece suits for foreign countries.’”

Khaliq received the Pride of Performance in 1968 for his services; however, according to Ijaz, his father was of the calibre of squash legends Jahangir Khan and Jansher Khan but he never received the same sort of respect.

Though Khaliq never expressed his bitterness regarding how he was treated throughout his life, Ijaz could sense that his father was not happy.

“He didn’t tell me anything, probably because he was upset about the way he was treated. He used to tell me whatever happened has happened, don’t talk about it,” he stated.

Ijaz believes his father did not get the kind of recognition he deserved. He shared that it took Pakistani media 27 years to run the first news about his father’s death anniversary.

“27 years after his death, I managed to get an announcement about his anniversary,” he stated. “Back in the day, PTV used to air clips of football, cricket and other sports from the archives, I asked them to run my father’s races, which were 21 and 10 seconds long, but they didn’t. After five years of constant efforts, a three-minute documentary was aired on the national television.”

The once fastest man in Asia did not even receive the kind of tribute on his death that he merited.

Khaliq had come back from Lahore in the last week of February and was complaining of excruciating backache.

The three brothers couldn’t watch their real-life hero in pain and took care of him at home for three days. Everyone asked him to visit a doctor, but he refused to do so. Finally, his mother ordered him to go to a hospital, to which he responded “let me die at home”. It angered Ijaz’s grandmother and she sternly instructed him to visit a hospital.

Khaliq was once the fastest man in the continent during his illustrious 20-year career

They took him to CMH Rawalpindi. On the third day of the admission, Ijaz was alone with his father. Khaliq was restless but his son knew little that his time had come.

As Ijaz served apple juice to his father as he was thirsty, his grandmother and paternal aunt reached there from Chakwal and started crying. “I asked them why they are crying, they replied, ‘your father is dying’ and just after a few minutes, he passed away,” he shared. “When we were leaving with the body, someone told me that President General Ziaul Haq has agreed to send him for treatment to England; however, we hadn’t applied for it. We didn’t see the letter ourselves, but we were informed about it.”

Khaliq’s last rituals were performed in his native village, as per his wish, where he was respected deeply. No one from the government or sports fraternity attended the funeral, apart from a few of his PSB colleagues.

“Probably government didn’t have time to pay any tribute to him,” he maintained. “We didn’t realise at that time but now I feel there should have been government protocol for my father. He was such a big name for Pakistan. It is not fair how he was treated.”

After a couple of months of his death, the family was offered a house and some monetary reward in Rawalpindi on his window’s name, which they got about a year later.

On one hand, no one paid tribute to the legendary athlete in the country, but on the other, Khaliq was among the 90,000 Pakistani soldiers who were the POW after the 1971 war.

Ijaz revealed that Singh himself went to meet him and they both cried. According to Ijaz, Singh asked the personnel deployed there to take special care of Khaliq as he was a star athlete.

Ijaz doesn’t want any monetary reward for his father’s achievements. He just wants the authorities to give him the warranted honour.

“My mother is 88 years and alive, no government organisation knows about it. If someone goes and tells her that her husband was a legend, will it cost something? She will only get happy,” he said.

He shared that it is his mother’s wish that the stadium that is being constructed in Chakwal be named after her husband. “If the government won’t name it after him, I will put a board on it myself and show it to her. The authorities can take it down later or do whatever they want with me, but I will do it,” he maintained.

Catch all the Sports News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Follow us on Google News.