Limits to Intervention

Pakistan could no longer be ruled with an iron hand, or the tactics of Zia’s days

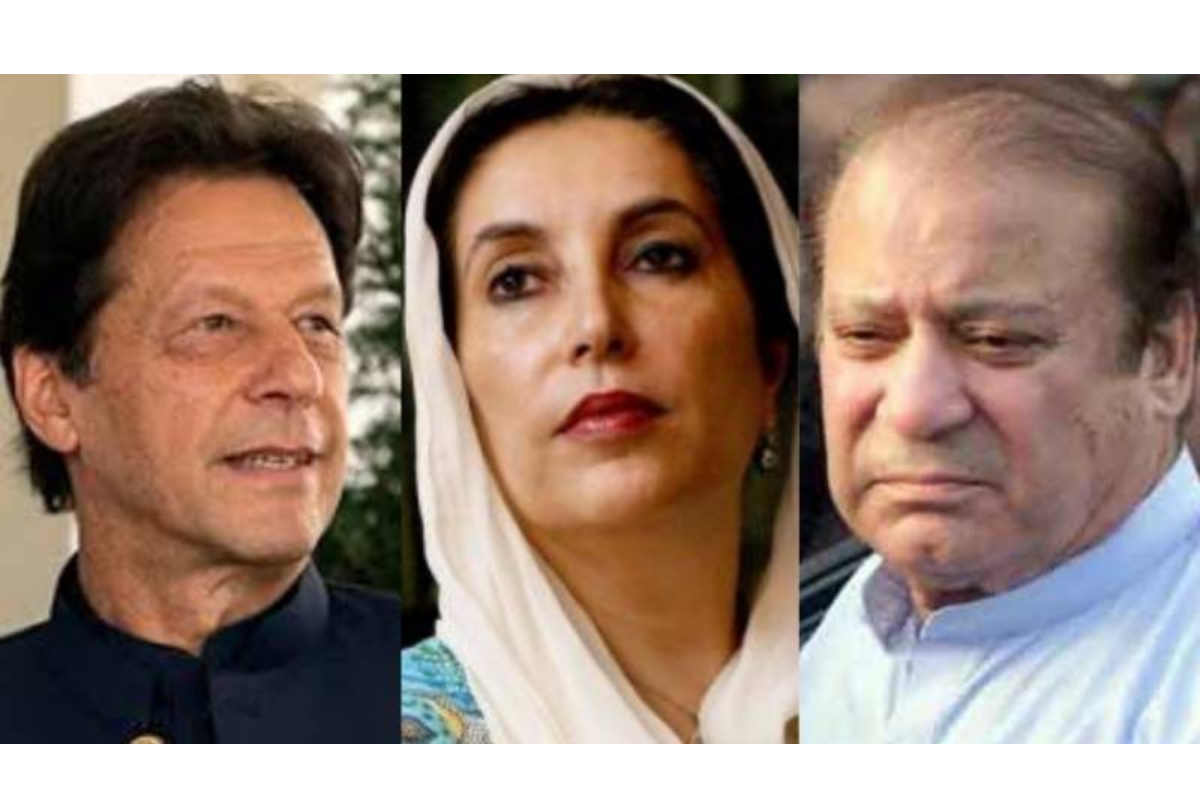

Pakistan’s history is replete with episodes of the state institutions confronting a popular leader, clipping his wings and ousting him from the political arena. This list of ‘political victims’ is long, the prominent ones being Fatima Jinnah, Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rahman, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif. Imran Khan is the latest entry on this list. The dominance of the establishment over political actors, whether through direct military rule or military-civil partnerships, is the hallmark of our polity. Over the years popular leaders have tried to break the gridlock on several occasions, but with little success. These days, Imran Khan is trying his luck.

The state does not tolerate the presence of a popular political leader who acts on his own, takes major policy decisions independent of the establishment, or challenges the supremacy of the deep state. As a true heir to the British Raj’s authoritarian tradition, the state manipulates, browbeats and buys political actors to fulfil its agenda. It buys or coerces local notables into switching their loyalties from one party to the other. It rigs elections to clear the way for its favourite collaborators to assume the prized office, but discards them once they outlive their utility. Those who defy them are sent to the gallows, like Bhutto, or are exiled, like Nawaz Sharif. Imran Khan has so far escaped such harsh punishment. Is this a sign of change?

The primacy of state institutions in Pakistan was rooted in the weak political base and socio-economic realities of the newly-created country. At the time of Independence, the present-day territory of Pakistan had a population of nearly 33 million, more than 90 per cent of whom lived in the rural areas. The state could easily put down any defiance. The population, at least in West Pakistan, was small enough to be governed with iron hands. The economy was largely dependent on agriculture, with a share of more than 90 percent in the national produce. The society was mainly tribal and feudal. Big tribal chiefs and landlords, being collaborators of the state, had, and continue to have an iron grip on their areas of influence. The genuine middle class and civil society were almost non-existent. In the vast expanse of feudal territory, a couple of cities such as Lahore and Karachi were like islands with a small population of the government-employed salaried class. In the early 1950s, for example, Lahore was a city of 3.5 million. Means of communication were limited. Until the 1990s, common people would wait for decades to get a telephone landline. The printing press faced strict regulations. Pamphleteering against the regime was treated as treason. Networking and forming political associations was an uphill task. And small underground political groups could easily be penetrated and busted by the deep state.

After Liaquat Ali Khan’s death in 1951, a nexus of the establishment and feudal/tribal lords fostered authoritarian rule with pretensions of parliamentary democracy. The state institutions jealously guarded their turf. They brought politicians into office, but vested them with only as much power as they wanted. Two bureaucrats, Ghulam Mohammad and Iskandar Mirza, did not allow any politician to work as Prime Minister for more than a year or so. In October 1958, army chief Gen Ayub Khan abrogated the newly framed first constitution of the country and imposed direct military rule. In the mid-1960s, when the small middle class of Karachi rose up in arms in support of Fatima Jinnah, the establishment easily crushed the movement. The state institutions did not yield to the Bengalis’ political demands, but accepted the secession of East Pakistan.

Notwithstanding the establishment’s supremacy, the fact remains that it has mostly ruled with the help of civilian collaborators and exploited the divisions within the political class to perpetuate and expand its political role. A not-so-covert military-civil partnership has been in force in Pakistan since the days of Gen Ayub Khan, with the establishment wielding the role of big brother or senior partner. Ayub Khan created the edifice of Basic Democracy to perpetuate his rule through civilian proxies. The establishment kept changing its civilian partners, but could not make do without them. The two have a kind of symbiotic relationship with each other. In East Pakistan, the establishment lost the battle because it did not find civilian partners, while in West Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto colluded with the establishment. Gen Zia capitalised on the subsequent anti-Bhutto political sentiment, alongside creating another support base comprising the religious right. Gen Pervez Musharraf crafted a partnership with traditional local influential politicians and found new partners by devolving power to the district level through a new local government system.

The country’s social and economic scenario had significantly changed by the time Gen Pervez Musharraf assumed power in 1999. There was a population explosion, with at least two megacities — Lahore and Karachi. The media was partly free. Means of communication had been transformed with the advent of the Internet in the mid-1990s. The country could no longer be ruled with an iron hand, or the tactics of Zia’s days. Gen Musharraf was smart enough to take into account the new realities. He eased restrictions by opening up the media. Private television and radio channels proliferated. And then 9/11 came as an economic boon for him. Remittances to Pakistan skyrocketed. Foreign loans were rescheduled. Big businesses thrived. The real estate sector witnessed an unprecedented hike. The middle class and civil society grew in size and power. When civil society put up a challenge to Gen Musharraf, he could not suppress it with force. For the first time in the country’s history, a rupture occurred between the military and judicial leadership. And the judiciary carried the day.

While the establishment’s role is well-entrenched, having governed the country directly or indirectly for the last seven decades, this time round it faces a formidable challenge in the person of Imran Khan, who has arguably emerged as the country’s most popular leader. The dynamics of society and polity have dramatically changed. First, the state cannot suppress a huge population of 230 million with force, as it used to do until the 1980s. The size of an assertive middle and lower-middle class has substantially increased. There are nearly six million serving or retired government employees and almost the same number of big and small traders. The middle class comprises Imran Khan’s support base. Z. A. Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto did not have this kind of support, as they had their roots in the working class or the rural areas. When Gen Zia cracked down on Z.A Bhutto’s supporters, the urban middle class belonging to the Punjab and Karachi did not actively resist military rule.

In the last decade, the expansion of social media and use of smartphones have rendered the government’s control over the media ineffective. With the social media platform, it has become easier for activists to network, form associations and take collective action. Curbing social media platforms will not be possible without harming commercial activity. In the presence of a Constitution that guarantees basic human rights and the judiciary, there is a limit to exerting informal pressure on the mainstream media and on political activists. The deep state can browbeat to an extent activists into submission at home, but it cannot silence a large Pakistani diaspora. Today, it is hard to imagine the state suspending the Constitution, suppressing an independent judiciary and rolling back media freedoms the way it did in the days of Gen Ayub Khan or Gen Ziaul Haq. There are new constraints on the establishment’s intervention in politics. The institutions making efforts to retain their primacy could face stiffer resistance this time than ever before, and need to make compromises with the changed realities.

Catch all the National Nerve News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Live News.

Read the complete story text.

Read the complete story text. Listen to audio of the story.

Listen to audio of the story.