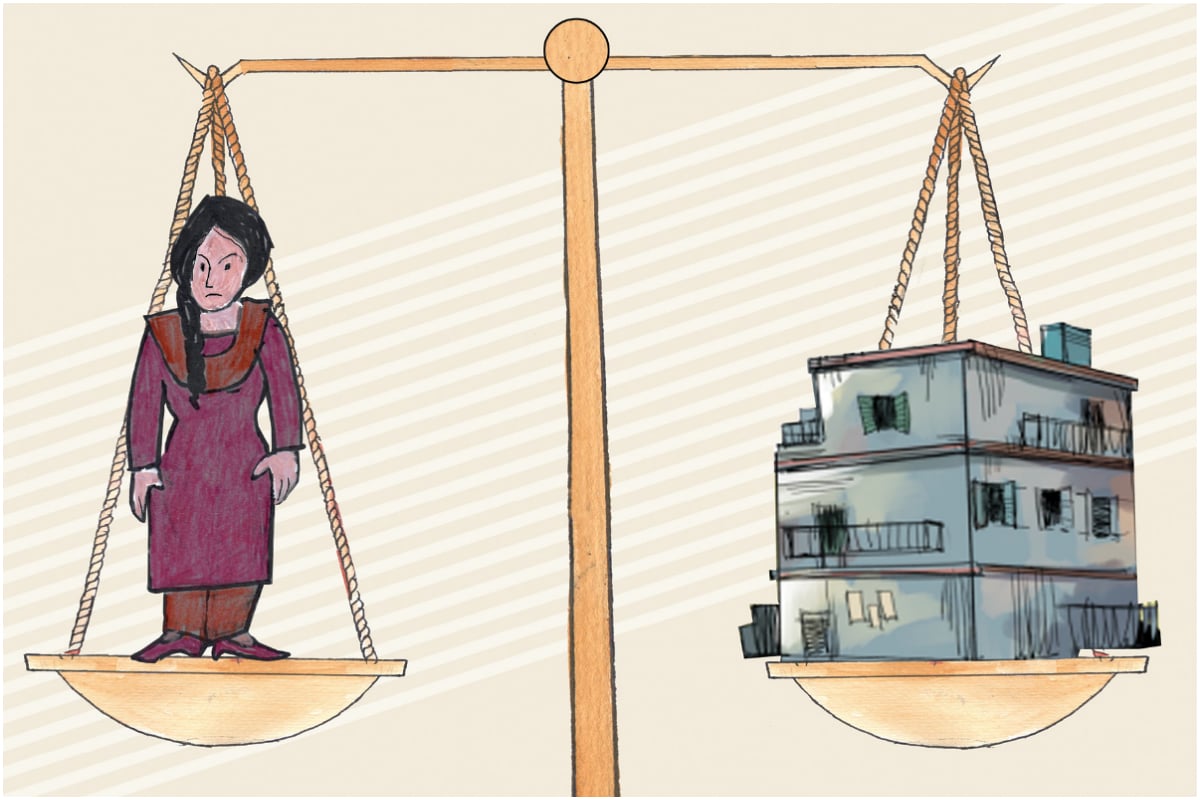

Right to Inheritance

In Pakistan, it is a common practise to deny women their inheritance, and many are forced to give up their rights unwillingly

Lahore: Depriving women of their inheritance is a common practise in Pakistan, where many women, whether from wealthy or impoverished families, are forced to submit to family customs and traditions and give up their rights unwillingly.

According to the Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18, 97 per cent of women [across Pakistan] did not inherit land or a house, while 1 per cent inherited both. Less than 1 per cent of women inherited non-agricultural or residential plots.

Normally, it takes years or decades for a woman to establish her inheritance rights in a court of law, but in Punjab, the office of a woman ombudsperson has been established under the Punjab Enforcement of Women’s Property Rights Act 2021 to ensure the provision of a speedy share of inheritance to women, but most women are unaware of it.

Every year, a 16-day international campaign against gender-based discrimination is held to raise awareness among women about various issues, including those concerning women’s property.

The campaign begins on November 25, International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and runs until December 10, International Human Rights Day.

Samira Samad, Secretary of the Punjab Department of Women Development, stated that her department is also running an awareness campaign against all forms of gender-based violence and discrimination.

She said that this campaign addresses issues such as economic violence, psychological violence, harassment, child marriage, and property sharing.

“There is the Punjab Enforcement of Women’s Property Rights Act 2021, which is being implemented by a female ombudsperson, and its purpose is to ensure women’s share in inheritance,” Samira explained.

“Women’s rights are prevalently killed in Pakistan’s Board of Revenue system; they are pressured and intimidated by the family into giving up their share in favour of their brothers; this specific act is designed to eliminate this menace,” she said.

She explained that a woman is not required to appear herself because a complaint can be filed on her behalf by someone else.

She stated that under Section 4 of the Act, any woman who is denied a share of property may file a complaint with the Ombudsman. The Ombudsman may refer the matter to the Deputy Commissioner, who shall be bound to conduct an investigation and report to the Ombudsman within 15 days. Following that, the Ombudsman may request additional records or objections from the complainant or the other party.

According to Samira, the ombudsman is required to issue an order, preferably within 60 days of receiving the complaint.

Fahima Shirazi is from the district of Bhakkar. When her father died in 2018, the property he left behind became a source of contention for her.

“My father died in September 2018, and we are three sisters and one brother; in December of the same year, the father’s property was transferred in the name of all of us siblings,” Fahima maintained.

The total property, according to her, included a market with 18 shops, a 10-marla commercial plot, a house adjacent to the plot, her father’s money in the bank, Rs. 1 million invested in a business, and so on.

She claimed that all of the properties were in Bhakkar, while she and her children lived in Islamabad. When the property was divided, her elder brother, who lived in Bhakkar, attempted to seize control of everything.

“I have two sisters, one in Karachi and one in Rawalpindi; they told me they want to file a property case against their brother, and I gave them a nod.”

“Because it was joint property, they filed a property partition case in civil court, but multiple litigation began between my sisters and brother, and one case snowballed into 11 cases.” “My brother also attempted to occupy my rented house in Bhakkar in 2020. I travelled from Islamabad to Bhakkar after my tenants informed me of an attempted illegal occupation,” she added.

Fahima stated that her daughter is a lawyer, so she began attending all of these court proceedings. His sisters also moved to Bhakkar in 2020.

“However, they made an agreement with my brother that he would give four marlas each to both of my sisters out of the 10-marla commercial plot, which I told them not to do, but they refused.”

Her daughter persuaded her to approach the Ombudsman Office in Lahore, which handles property disputes for women. “I immediately came to Lahore and filed my plot case through my lawyer daughter,” she said.

Hearings were held, the court sought reports from the Deputy Commissioner of Bhakkar and the civil court, and she succeeded in getting possession of her plot in January 2022.

“The court also decided the case regarding the rest of the inherited property in my favour in June 2022, after taking into account the relevant evidence,” Fahima added.

She regretted wasting three years of her time and money in civil court.

She claimed that the women were unaware of where to go in such a situation, adding that she was lucky enough that her lawyer daughter accompanied her and assisted her.

Fahima’s daughter, Advocate Maryam, believes that if Ombudsman courts are established in every district, women may not face as many difficulties in obtaining their share of inherited property.

Concerning cases such as Fahima Shirazi, Samira Samad stated that the Department of Women’s Development has a helpline number, 1043, that receives calls. In the month of October alone, 11 per cent of all calls received were property-related. These are either complaints or information requests.

What else does the ‘Punjab Enforcement of Women’s Property Act 2021’ say?

According to Section 5 of the act, the ombudsman shall ensure that the order is carried out by directing police and district administration officials to restore possession of the property to the complainant.

While Section 9 empowers the ombudsman to direct any executive of the state, including the concerned deputy commissioner, to carry out orders issued to the letter where the complainant’s property is located.

In addition, Section 11 states that no court or authority shall call into question the legality of proceedings initiated after the ombudsman’s orders have been issued or grant a stay or interim order thereon.

What are the penalties for not contributing to the property?

In regards to the disputes concerning women’s share in inheritance, Advocate Syed Sajjad Haider Naqvi said, “Before giving a woman a share in the property, it will be seen what religion she belongs to; if she is a Muslim, her sect would be determined because in some sects the distribution of property is a little different, especially if there is no son in the share of inheritance.”

According to Naqvi, if a woman is not given a share of inherited movable or immovable property, there are penalties under Section 498 (A) of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) 1860, which can range from five to ten years in prison or a fine of Rs. 1 million, or both.

He added that women are denied their share of inheritance in various ways and that they are sometimes married to the Quran. Such cases have primarily been reported in Sindh and South Punjab. This is a serious offence under Section 498 (C) of the Pakistan Penal Code, punishable by imprisonment for three to seven years and a fine of Rs. 0.5 million.

When property is distributed, it is claimed that the woman was given a dowry on marriage and thus no longer has a share in the remaining property, or that when inheritance is divided, the elder woman of the house is forced to go to the patwari. To obtain inheritance, emotional blackmail is also used, and it has been observed that girls are forced to marry too young or while mentally ill in order for the property to remain in the family.

“This is also a violation of Sections 498 (B) and (C) of the Pakistan Penal Code,” he concluded.

Catch all the National Nerve News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Live News.

Read the complete story text.

Read the complete story text. Listen to audio of the story.

Listen to audio of the story.