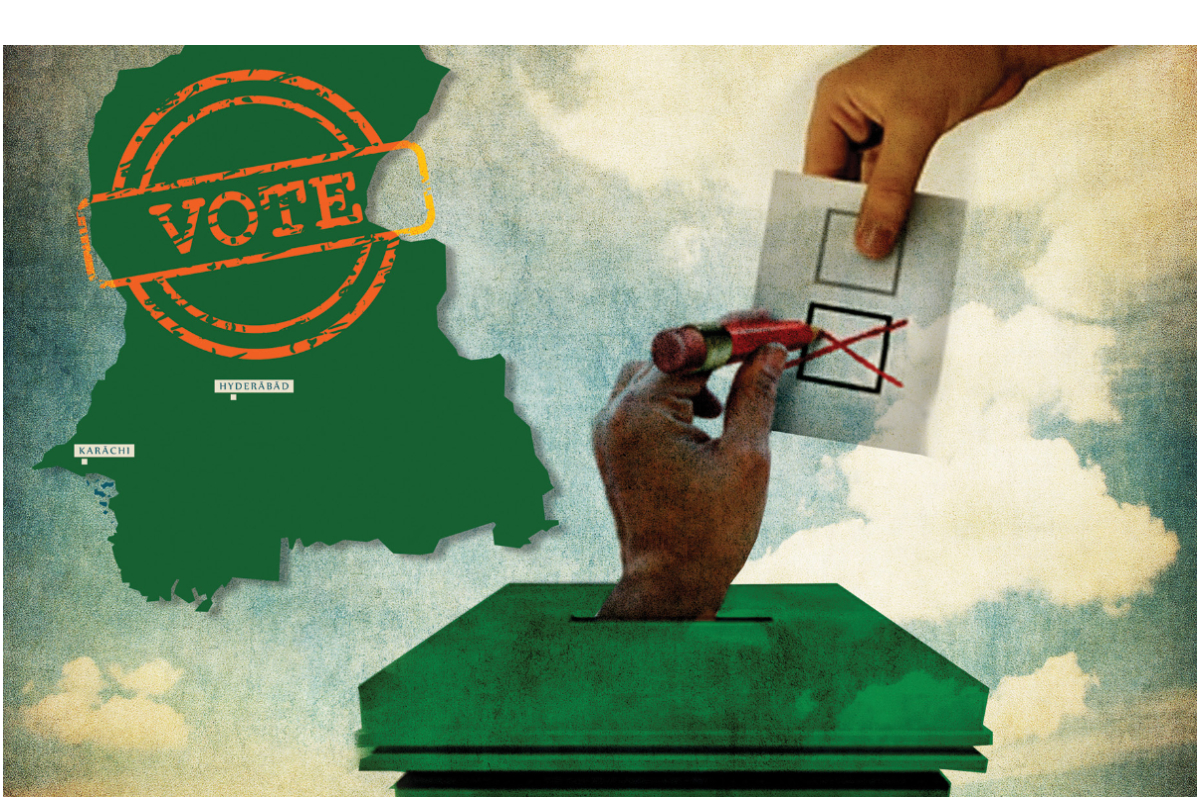

A ‘Sham’ Election

The local government polls in Sindh expose glaring flaws in our electoral system

The recent local government (LG) elections in Sindh have again reminded us of the serious flaws in our electoral system and the need to reform it to ensure legitimacy of the electoral exercise and a stable democratic process.

These elections, held on January 15 after multiple delays, were marred by controversy over demarcation of electoral boundaries, a low turnout of voters, complaints of bogus voting and alleged doctoring of results at the stage of the compilation of the final tally.

There is a general view that democracies perform better when more people cast their votes.

Pakistan is known to have one of the lowest voter turnouts in the world, but the voter turnout at the recent LG elections in Karachi and Hyderabad was the lowest ever recorded.

More than 75 years have passed since our Independence, but we have failed to establish a free, fair and transparent electoral system.

A video clip recently went viral in which men from a political party were stamping ballot papers for bogus voting at a polling station in Karachi.

The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and the Jamaat-e-Islami have staged a protest against the alleged doctoring of the final results of certain local wards—results of more than 20 wards are considered controversial—at the office of the district‘s returning officer.

This has particular significance as the numbers matter in the election of the mayor.

The two parties allege that the results issued by the returning officer do not match with the ones officially given to them at the polling stations.

It is certainly hard to justify the delay in the announcement of election results by the returning officers for more than 24 hours after the polling concluded, given the small size of electoral constituencies and an abysmally low turnout.

What happened in the Karachi polls reflects the overall abhorrence of the provincial government with devolving some of its powers to the LGs. Sindh’s LG system is perfunctory to say the least, with few municipal powers devolved to the LG by the provincial government.

The Karachi municipal body has no authority over the collection of solid waste or supply of water to the residents of the megacity. These powers are in the hands of the government departments under the administrative control of the provincial government.

Housing and the city’s public transport system are provincial subjects. And the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) has been hesitant to hand over even that minuscule authority to local representatives.

The previous local councils completed their tenure in 2020. For two years the provincial government ran the LGs through handpicked people and bureaucrats. On the insistence of the higher judiciary the provincial government reluctantly moved to hold voting in two stages.

However, in Karachi and Hyderabad, where the ruling party has a small vote base, it tried to postpone elections till the eleventh hour, until the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) finally put its foot down and forced it to conduct the exercise.

The official statistics of the January 15 LG polls in Karachi and Hyderabad divisions are yet to be announced. The journalists who covered the polling believe that the voter turnout was between 10% to 25% in different urban localities.

In rural or semi-urban suburbs, however, the participation was relatively higher, exceeding 40%.

The fact that a large majority of eligible voters abstained from casting their vote manifests their distrust in the exercise, which was visibly skewed and loaded against certain ethnic communities and political parties in the two cities.

It was a contest among four to five main candidates in Karachi and Hyderabad.

The PTI, the PPP, the Jamaat-e-Islami and the Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) were in the run, besides several independents and other smaller parties, including the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F), and the Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) in certain wards.

Given the first-past-the-post system, the winner in each constituency, in most cases, obtained fewer votes than the combined count of those who lost the election.

As per general observation, less than one-fifth of the total registered voters cast their vote in the two cities. Most elected councilors, therefore, have a mandate from no more than 5-7% of the total registered voters.

Now the question is how can this electoral exercise be termed legitimate, when the winners do not represent the majority of the population?

The political parties of urban Sindh have been agitating against the 2017 census in which, they allege, the population of Karachi was undercounted, so as to deprive the people of the city their due share in the national and provincial assemblies, in addition to finances and jobs allocated on the basis of population.

Additionally, the provincial government has carried out a crooked demarcation of local constituencies, aka wards, in a manner that the localities inhabited by the Urdu-speaking population are under-represented in the municipal bodies. This is the worst kind of gerrymandering.

In Karachi, a constituency, ie, a ward, comprising non-Urdu speaking ethnic communities, constitutes a nearly three times smaller population than the one where Urdu-speaking people are in the majority.

In other words, three votes of the Urdu speaking (Mohajir) community are equal to one vote of the non-Mohajir communities. Obviously, the provincial government’s purpose was to reduce the number of councillors elected from certain areas.

This makes a difference because chairmen of the union councils, in turn, will elect the mayor of the city. Given these circumstances, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM-P), having its main support base in the Mohajir ethnic community, boycotted the election.

Resultantly, the enthusiasm of voters was manifested in the number of abstentions on the voting day.

The skewed demarcation of wards in Karachi is against the basic principle of the equality of votes, and neither the ECP nor the higher judiciary was moved in violation of the principle of the equality of votes at such a large scale while delimiting local constituencies.

Only in very special situations do Section 20(3) of the Elections Act 2017 allow the ECP to ignore the 10 per cent plus and minus formula of population. When it comes to Karachi or urban Sindh, the national institutions seem to be blindfolded.

The blatant use of the administration in influencing the outcome of the LG elections can also be gauged from the fact that an unprecedented high percentage of councillors—almost 34%— from the Hyderabad division returned unopposed; more than 90% of them belonged to the ruling PPP.

In the 2015 local elections, only 16% candidates were elected unopposed. In the rural areas, the administrative machinery was allegedly employed to coerce the aspiring candidates to withdraw in favour of the nominees of the ruling party.

Those who defied the pressure were arrested and faced the wrath of the police. The ECP seems to have given the PPP an open field in Sindh, forgetting the strict standards it had applied a year earlier in the by-elections in Punjab’s Daska constituency.

The ruling PPP has enacted self-serving LG legislations in Sindh, stacking the local tiers of government with its lackeys. Now there is a kind of neo-feudalism at work at the LGs.

First of all, the PPP amended the law several times to ensure that the LGs are deprived of substantive powers and they remain at the mercy of its provincial authority.

Ironically, now in the Sindh LG system, five directly elected members of a ward will select six other members of the ward on the seats reserved for women, labourers or peasants. In the 2002 LG system, these seats used to be filled through direct elections.

Sindh’s LG system and the way local elections have been conducted in Karachi and Hyderabad are a typical example of how the constitutional provisions that guarantee equality and socio-economic and fundamental rights for every citizen, have been glaringly violated in favour of the elite.

In a society dominated by big landlords, the dice is already loaded against the common man who cannot challenge the authority of the rural gentry, and the nakedly crooked laws and use of executive authority to bend whatever little legal space is available to them make the situation even worse, as was evidenced by the results of the recent LG polls.

These elections are more likely to further alienate a vast majority of urban Sindh than to serve the original objective of making governance more participatory. The way these elections have been conducted is a recipe for perpetual urban unrest in the coming days.

Catch all the National Nerve News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Live News.

Read the complete story text.

Read the complete story text. Listen to audio of the story.

Listen to audio of the story.