Our Educational Dilemma

Educational reforms are long overdue, including the key reform of enforcing a single national curriculum

Pakistan’s socio-economic indicators, economy and governance have been going through a systemic decline. The consequences are evident not only from the falling performance indicators, but also the country losing ground internationally to other competitors. While Pakistan’s governance framework has been confronting many issues, the educational challenge is the most formidable one and probably the root cause of increasing lack of efficiency as well as aggravating ills in the society.

There have been weaknesses in the country’s education system since independence, but the decline has been more obvious and pronounced in the past 50 years. Until the 1970s, the public school system was working fairly well in fulfilling the educational needs of the majority of the population. All it required was to ensure the system’s expansion and growth to cater for the needs of the population increasing at a fast growth-rate and enhance the universality of education, particularly at the primary and secondary levels.

Paradoxically, while Pakistan’s population has increased around four times (from 64 million in 1973 to estimated 235 million today), the public sector education has undergone a massive deterioration, and the state instead of taking measures to meet its fundamental obligation of provision of education to its citizens, preferred to outsource it to the profit-oriented private sector. Over the years, all serious social thinkers and reformers have been identifying the growing weakness and loopholes of the education sector and emphasizing the need for comprehensive reforms, but no significant effort has been made by the federal or the provincial governments. Also, there is absolutely no coordination between central authorities and provinces and education in Pakistan altogether remains a directionless and disjointed sector as following the 18th amendment it has become a provincial subject.

To start a reform, the first prerequisite is the spending on education. Pakistan is among the countries with lowest per capita spending on education. According to international standards, the minimum budget a country should be allocating to education has to be around 4 percent of the GDP. In contrast, education spending in Pakistan in 2021-22 is at 1.77 percent of the GDP — the lowest in the region. Successive governments have not been able to increase budgets on education (it has continued to remain around or less than 2 percent of GDP). This is a serious dilemma where other national priorities take precedence than spending on educating the children.

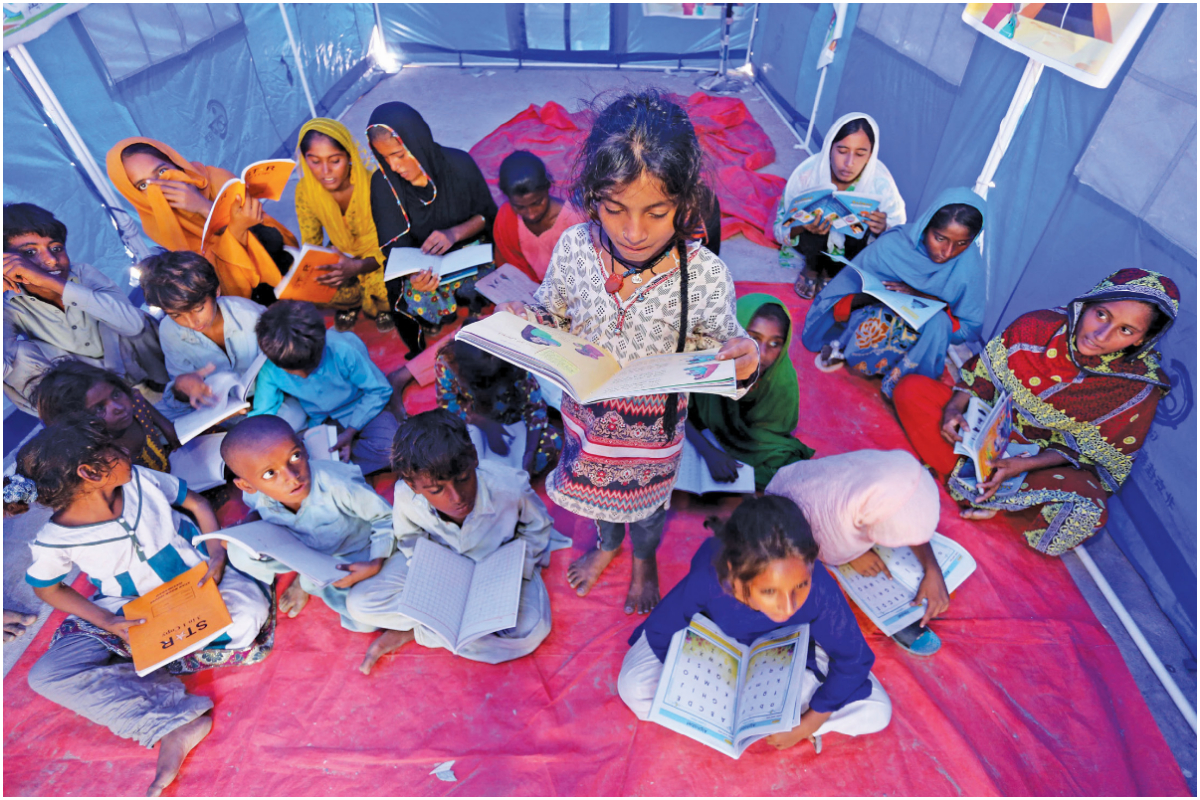

The rate of enrollment of students for formal schooling remains low. Alarmingly, according to a report of the National Commission on the Rights of Child (NCRC) released in December 2022, an estimated 22.8 million children between the ages of 5 and 16 years (almost ten percent of the country’s total population) are out of school in Pakistan. This makes Pakistan a country with the second highest number of children outside schools and 44 percent of these out of school children are engaged in labour or begging.

Apart from a sizable number of children not going to or dropping out from the schools, Pakistan has not been able to achieve uniformity in its education system and curricula. Public and private sector education is common in the world. But it’s a universal practice in the successful educational systems that the state takes care of primary and most of the secondary schooling, while at the higher or tertiary education, a combination of public and private universities and degree awarding institutions are available for accommodating the students.

In Pakistan, however, three totally different streams of education at basic schooling level are working with the approval of the state. These include (i) public sector schools (unable to enroll all students and deficient in capacities), (ii) private sector schools following their own standards, disciplines and fee structures (mostly catering for higher and upper middle class strata) and (iii) Madrassas providing education according to their own religious fiqh (version). More strikingly, 62 percent public sector institutions meet educational needs of only 56 percent students in Pakistan, while 38 percent private institutions have to accommodate 44 percent students.

Around 40,000 madrassas remain another unaddressed challenge of Pakistan’s educational sector. It should be recognized that madrassas are playing a supportive role to the government and society by providing education and boarding to more than 2.5 million students in Pakistan. However, due to the lack of integration and mainstreaming of these madrassas into the national education system, such a large number of students qualifying from madrassas remain deprived of opportunities for employment and professional development.

In view of the grave flaws in primary and secondary education, the tertiary sector or university education in Pakistan has been underperforming. The total number of students enrolled in 186 universities and higher education institutions are 1.576 million or only 0.68 percent of the population. There is also a shortage of technical and vocational training institutions in Pakistan which could be the backbone of industrialized and commercial sectors.

Gross discrepancies in the education sector are impeding social and economic transformation in Pakistan. The much required shift from an agriculture-based country to a modern industrial economy remains fraught with difficulties due to lack of educated and skilled middle class and manpower being produced by other developing countries in the region such as China, India, Malaysia, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The educational shortcomings also make it difficult for Pakistan to grab its due share in the demand of white- and blue- collar labour in North America, Europe, Middle East and Japan. In addition, the lack of properly skilled manpower is one of the key hindrances to the flow of FDI by multinationals in Pakistan.

Currently, Pakistan is passing through a difficult phase with political uncertainty and grave economic crisis. The national and provincial elections are also due this year, which would hopefully provide a way out of current political impasse. As soon as this phase is over, the Parliament and the executive should launch serious reforms in Pakistan’s education sector.

The reforms have been long overdue. There should be uniformity in the provision of education for all citizens. This is high time to go back to a single curriculum meeting requirements of the entire nation and a uniform homegrown examination system both for public and private sectors. Madrasa education’s mainstreaming and integration into the national system cannot be left into abeyance for an indefinite time. Focus on increasing enrollment is important and incentives should be introduced for bringing marginalized and vulnerable segments of the society into the realm of education.

The reforms in the university and higher education sector should aim at grooming the younger generation conforming to the national development and economic needs. A special initiative is required for establishing a nationwide network of vocational training institutes as it would not be possible to make industrial and commercial progress without developing a skilled and trained labour force.

Above all, transforming the mushrooming growth of the population of Pakistan into a productive human resource is not possible without significant increase in spending on education for the country’s future. And, the time for taking these vital measures is not unlimited.

The writer is a former ambassador of Pakistan to Afghanistan

Catch all the National Nerve News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Live News.

Read the complete story text.

Read the complete story text. Listen to audio of the story.

Listen to audio of the story.