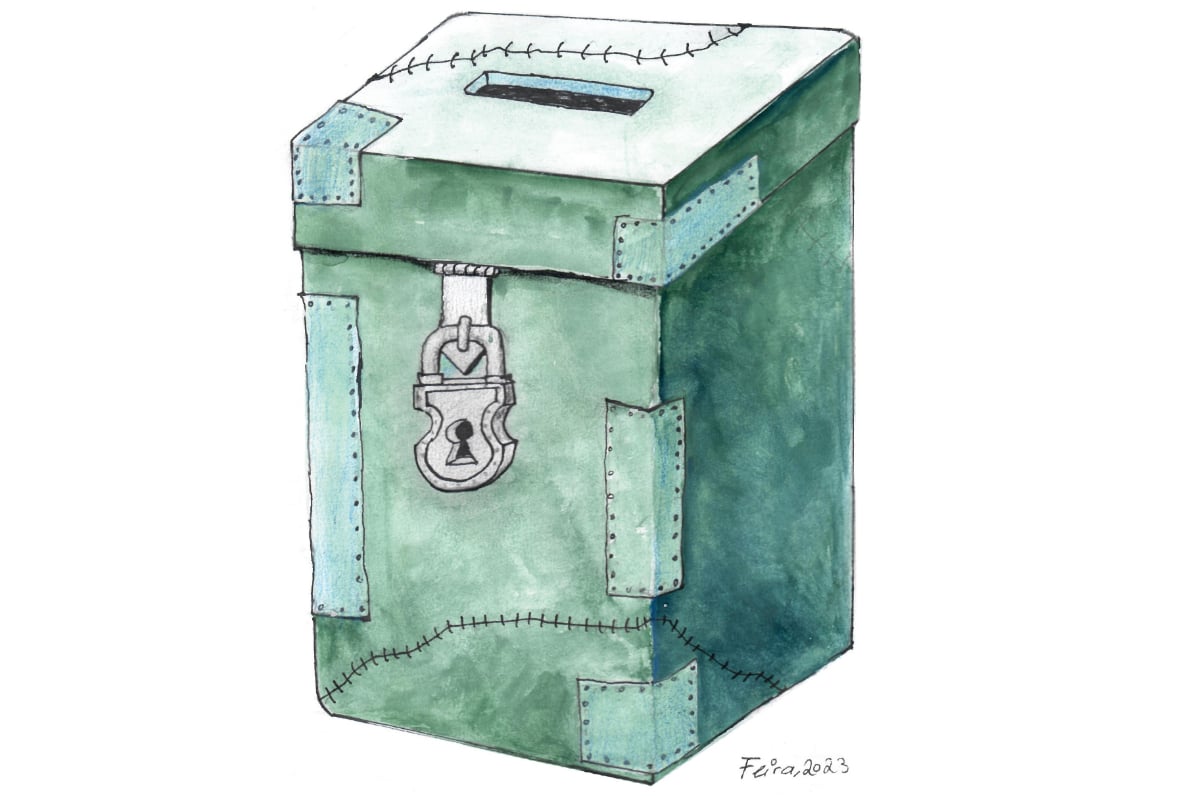

A Vote Already Cast

The current electoral system remains skewed in favour of the feudal elite

A few days ago, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar appealed to expatriate Pakistanis to remit as much money as they could muster to Pakistan’s foreign accounts and allow a charity organisation to collect two billion dollars from them in order to meet the country’s acute foreign exchange shortage. Ironically, these are the same overseas Pakistanis whom the present government has deprived from voting electronically. The PTI government had legislated to entitle the huge expatriate community — many of whom still have family in their home country and yearn to remain involved with it — to vote, and made elaborate arrangements to enable their participation in the elections. But soon after assuming office, the government of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif nullified the concerned sections of the law empowering expatriates to vote. The ruling alliance, mainly comprising the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N), fear that the majority of overseas Pakistanis favour the Pakistan Tehrik e Insaf (PTI), and it would therefore be disadvantageous for them if they were allowed to cast their votes. One can ascertain from this alone how dubious the democratic credentials of our political actors in power are: they want an electoral system that favours them at all cost, no matter how unrepresentative it might be.

In fact, Pakistan’s entire electoral system is skewed in favour of a certain class and has little to offer to the middle class or the poor in terms of their participation in the power structure. It has been fashioned to suit the interests of the country’s small elite and its monopoly of power. Electoral laws and the entire process are largely exclusionary in nature, discriminating against the lower-income sections of society, religious minorities and women. No wonder, Pakistan has one of the lowest election turnouts in the world – 40 to 55 per cent of the total registered voters cast their vote in the general elections, which reflects, among other things, the people’s low confidence in the system. For instance, the turnout was 35.4 per cent in 1997, 41.8 per cent in 2002, 44 per cent in 2008, 55.02 per cent in 2013 and 51.7 per cent in 2018.

A major flaw in the system stems from the fact that a minimum turnout is not fixed in our election law, and in most cases, a party forms a government by securing less than 20 per cent of the total registered votes. Let us imagine a situation, as has often been witnessed in Pakistan, that the winning party bags 35 percent of the votes cast in an election with a 50 per cent turnout. This means the single largest majority party obtains only 17.5 per cent of the total tally. At the height of its popularity in the 1970s, the PPP bagged only 37 per cent of the votes cast. In 2002, the PML-Q formed the government, although it had obtained only 25.7 per cent of the total cast votes. In 2013, the PML-N won the majority, by obtaining 32 per cent of the total polled votes. In 2018, the PTI, the single largest party that went on to form the government, secured 32 per cent of the total polled votes. Thereby, no political party in Pakistan has ever represented the majority — ie. above 51 per cent — of the population. According to Sarwar Bari, an eminent election researcher, more than 50 per cent of the votes polled go to waste in our system. Similarly, he says, under the present system, a candidate can become a member of an assembly by obtaining as low as two to three per cent of the total registered votes. This mostly happens in Balochistan and the far-flung areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, or in Karachi when the MQM boycotts the election.

The existing electoral laws, which recognise a low-turnout election as valid, reinforce patriarchal society, keeping women out of the political process in many regions. In many conservative regions of our country, women are not allowed to cast their votes. In order to ensure the participation of women in the voting, the election law stipulates that if women’s turnout is less than 10 percent of the total polled votes in a constituency, the Election Commission of Pakistan may declare the results void. But a technical sleight of hand has been played to condition the clause to suit those in power. Currently, two different methods are used to calculate turnout – one for the general turnout, and the other for women. For the general turnout, the Election Commission divides the polled votes by the number of total registered voters, but to calculate the women’s turnout, the number of women’s votes are divided by the polled votes. In this way, women’s turnout is raised to avoid re-polling.

For the common man, there are many disadvantages in the first-past-the-post method. In our tribal and semi-tribal society, clannish relationships influence voting behaviour. In most constituencies, members belonging to the largest tribe or biradari in an electoral district invariably tend to win the seats. Political parties also choose candidates from the largest clan inhabiting the area. The party-vote combined with the individual’s vote (based on biradari or his/herinfluence) makes for a winning combination. For example, in the Punjab, the Jat, Rajput, Awan, Arain and Syed are major influential clans and dominate the electoral map. A major biradari may constitute 20-40 per cent of a constituency but owing to the first-past-the-post system, it outweighs more than a dozen other biradaris living there. It is a common observation that clan-dominated electoral politics has negative implications for governance and the judicious use of the government’s resources.

In feudal-dominated regions such South Punjab or rural Sindh, and in the tribal belt of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the electoral system favours feudal lords and tribal chiefs, who by the dint of their traditional stranglehold over the masses leave little room for ordinary people to challenge them in any electoral battle. Those who dare to oppose the traditional elite have to face punitive action and persecution at the hands of the administration. Thanks to the constituency-based polling, so-called ‘electables’ or local notables have a stranglehold over electoral politics; and they are manipulated by the establishment to make or break political parties.

In order to make our electoral system truly representative, the law should place a limit on the minimum percentage of the turnout in a constituency (say at least 33 per cent) for an election to be valid. In case of a low turnout, a re-election should be conducted. Once the bar is fixed for a minimum turnout for an election to be legitimate, candidates and parties will be compelled to encourage more and more women to cast their vote. Secondly, the first-past-the-post system needs to be discarded, and it should be made mandatory for a winner to attain at least more than 50 per cent of the polled votes. In case no candidate succeeds in receiving the mandatory percentage of votes in the first phase, a run-off election should be held among the two top contenders. The cost of holding an election may go up, but it has a value for making the democratic process authentic. The requirement of obtaining 51 per cent of the cast votes will weaken the stranglehold of the biradaris and feudal lords who will be forced to reach out to smaller clans and the larger audience and do some political bargaining with them, thereby making the process more inclusive.

The other option is for Pakistan to abandon the present constituency-based system and adopt proportional representation, which is more inclusive and egalitarian in nature. Envisage a scenario in which each province is designated as one electoral constituency and the parties winning a certain percentage of cast votes in every region are allocated seats (as per their lists of nominations) in the assembly as per the percentage of the votes they received. In this way, many small ideological parties, in our case Islamist, socialist and sub-nationalists, will get their due share in the assemblies along with mainstream parties. At present, the votes of these parties are scattered all over the country or a province due to which they do not win seats as per their total strength and remain out of democratic institutions.

A proportional representation scheme will allow for the mainstreaming of regional parties and for ideological people to have a voice in the law-making bodies. This will also discourage local concerns from influencing national politics. Our MPs take little interest in national issues and remain more obsessed with local issues and development works in their small electoral districts. They jealously guard their local turf by meddling in administrative affairs at the local level. That is why the MPs oppose a powerful local government system, as they see it as a threat to their exclusive hold on power in their respective regions.

A powerful local government elected through small constituencies alongside national and provincial assemblies elected through proportional representation could be a good combination for enhanced political participation and effective democratic governance. It is not that the local elite will become totally irrelevant in the proportional representation system, because the parties, in any case, will need the support of locally influential people to gain the maximum number of polled votes. The clout of local notables will substantially diminish in national politics, but they will have a meaningful role to play at the local level through municipal governments. One may argue that under proportional representation, candidates will buy their nominations by bribing party heads, but the same holds true for the present constituency-based elections in which candidates, in many cases, get tickets by bribing the high-ups in the parties.

Whether we choose the principle of mandatory 51-percentage votes for winners, or proportional representation, either of the two can increase the quantum and quality of representation. The issue is that our parliament is dominated by the parties and the elite who have a vested interest in perpetuating the present system and do not like to make any amendments to it. The status quo suits them, though it goes against the interests of the middle class and the poor. And this discussion will remain academic unless a strong movement is waged by those who are suffering from the current arrangement and force the powers to be to carry out reforms.

Catch all the National Nerve News, Breaking News Event and Latest News Updates on The BOL News

Download The BOL News App to get the Daily News Update & Live News.

Read the complete story text.

Read the complete story text. Listen to audio of the story.

Listen to audio of the story.